HTTPS for Humans

I always felt uneasy about HTTPS. I knew it worked. I knew all my web stuff needs to use it. Browsers now tell you explicitly that you’re in the scary land of “Not Secure” when you visit a website not using HTTPS.

But I never knew exactly what happens under the hood. When I looked around the internet to find answers, Google presented me with a ton of ads trying to sell me certificates and some technical articles diving very deeply into the gory details and escaping my short attention span. But I forced myself through it and decided to write a human-friendly overview of how HTTPS works, to help myself remember it and maybe help someone else understand it.

What’s HTTPS?

HTTPS is simply HTTP with some encryption applied on top. In a normal communication via HTTP, the data is transmitted in plaintext, so if someone decided to “listen” to your communications over the network, they’d see all the data in plain sight.

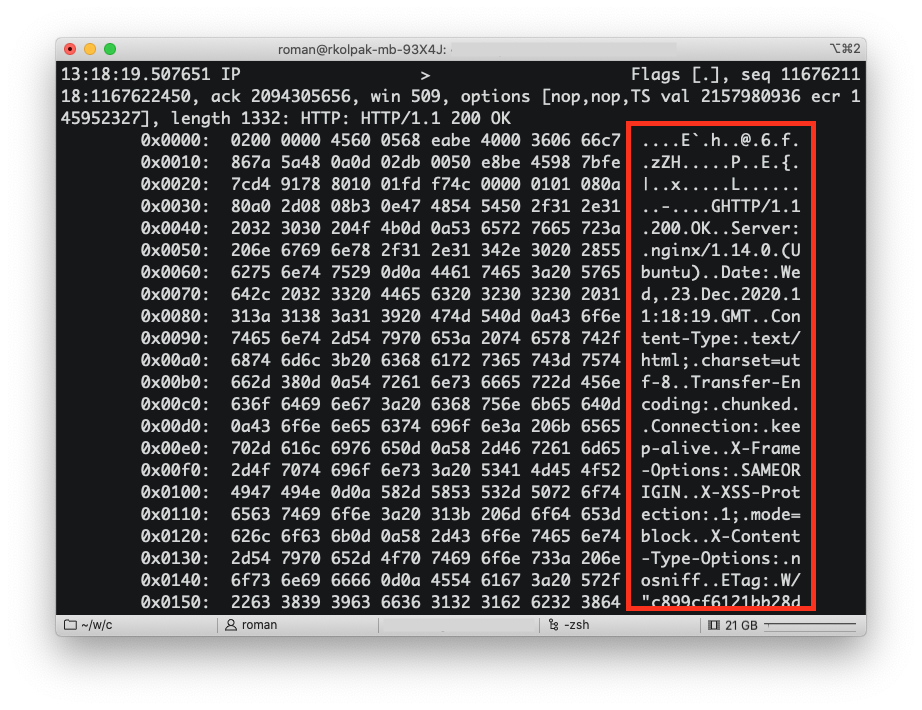

To demonstrate this, let’s use tcpdump tool to sniff some traffic we’re exchanging with a website using HTTP (without the S):

See how you can read the bits and pieces of the HTTP response? It’s all in there, with the HTTP headers, HTML of the response body, cookies, everything in plain text. If the request you sent to the website included sensitive data, such as your password for logging in, that data would be in plain text too!

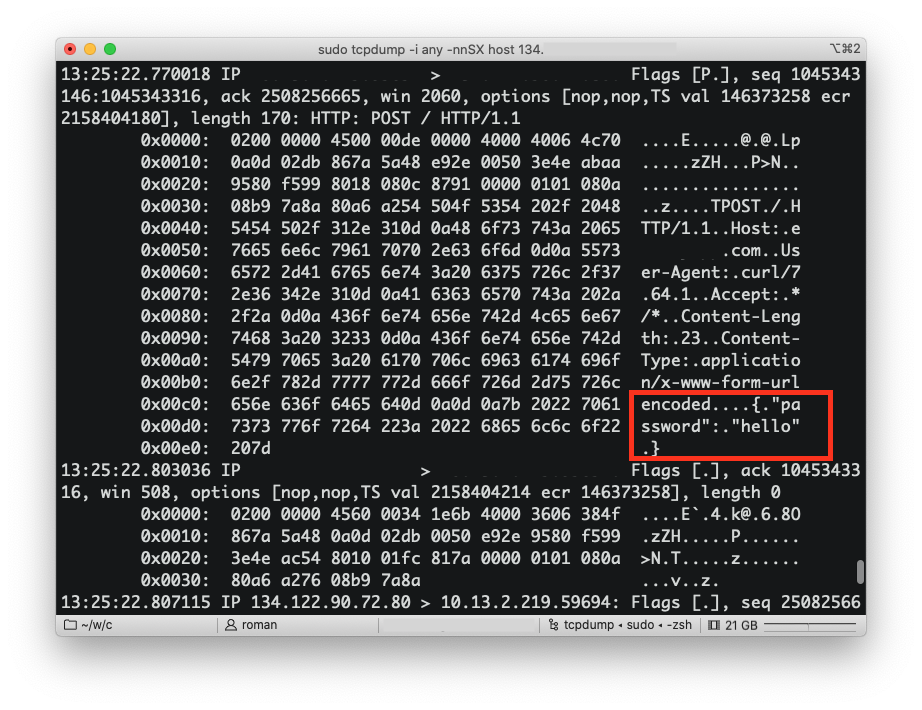

Now that’s take a look at how this looks like when using HTTPS instead of HTTP. If we send a request to a different website, which is a good citizen on the internet and is using HTTPS, and look at the raw packets, this is what we’ll see:

See how it’s all gibberish now? That’s because it’s the same HTTP requests and responses, but encrypted. That’s it! That’s HTTPS.

Encryption

So it’s all very simple on the surface - we’re sending the same good old HTTP requests and get the same HTTP responses from server, but the contents are now encrypted instead of being sent in plain text. Pretty straightforward.

This is where the straightforward part ends, though. Because HTTPS is just HTTP with encryption, in order to understand how it all works together you kinda have to dig into the details of the encryption methods to build a more or less complete intuition of how it works.

A lot of complexities of the cryptography and TLS (that’s the official name for the encryption layer of HTTPS) are easier to understand when you sit down and try to solve the problem of secure communication over HTTP from scratch. Let’s see if instead of reading through complex TLS RFCs we can learn by doing.

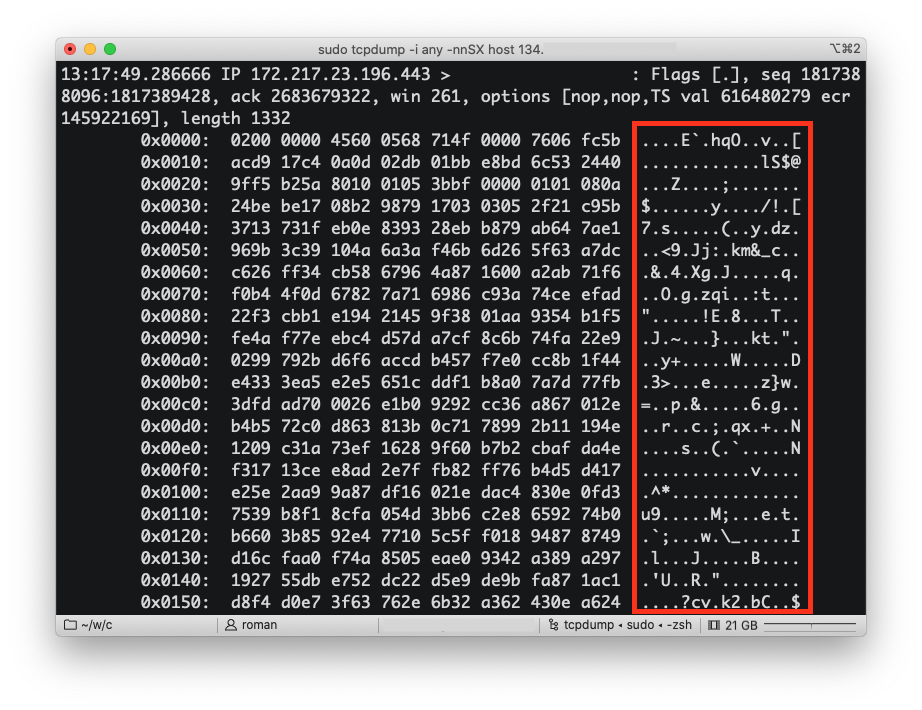

The problem we’re going to solve is this - a user wants to talk to a computer (a website’s server) on the internet and the communication needs to be secure, so any 3rd party having access to all the contents of our communications should not be able to understand any of it.

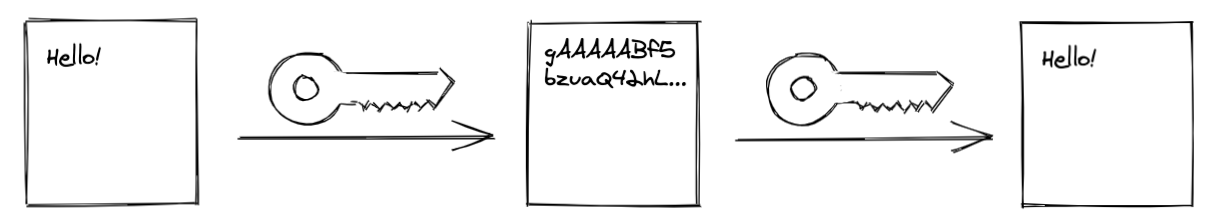

We already know that encryption is the answer — we just need to encrypt our data! Sounds easy. Let’s use the simplest form of encryption - a symmetric-key algorithm. This is the older form of encryption – the data is encrypted and decrypted using the same piece of information - a “key” which is a string of characters.

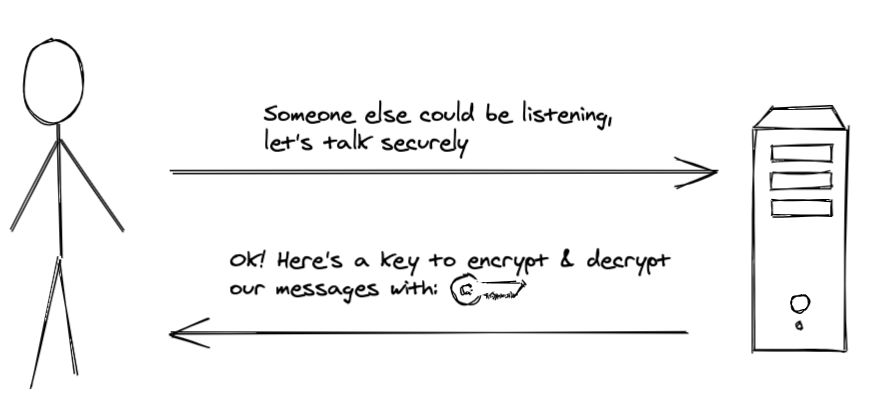

Now we need for both parties in our communication link to know this key, so that they can decrypt the messages sent over the wire. How do you accomplish that? You kind of have to send this key over the wire, too. So let’s have our website send the key for encryption on the initial “hello” message to the user before the encryption can be applied to the messages:

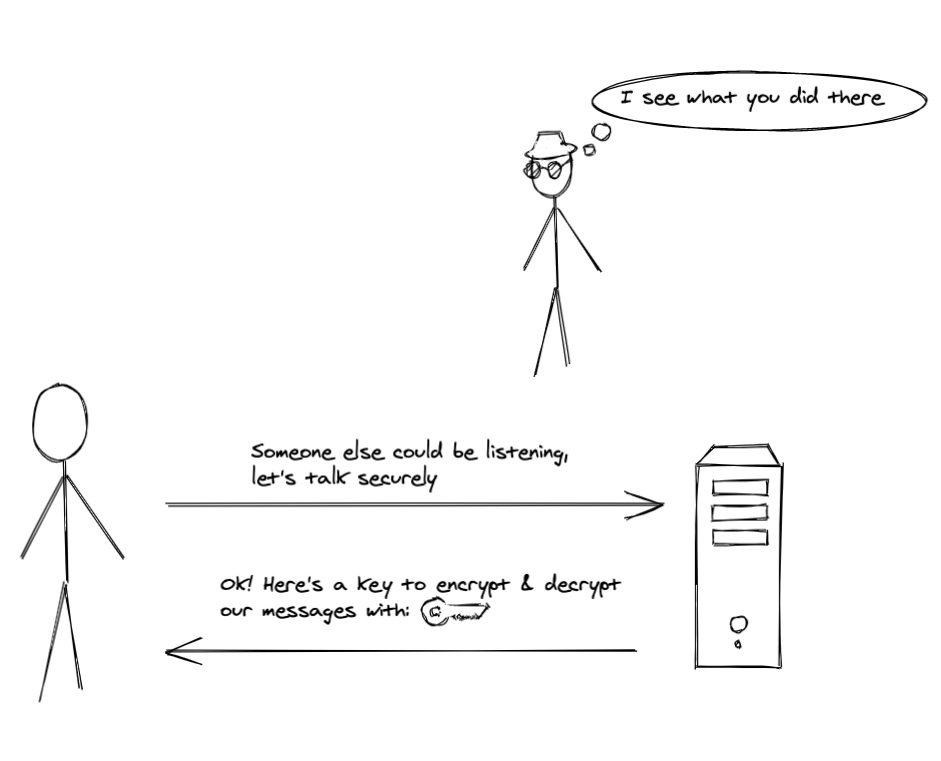

But remember, we have a malicious party sitting and listening to our communications, and if they were looking patiently, they saw that the message from server to the user had an interesting piece of data in it and will probably be able to deduce that that data was an encryption key in plain text. Even though all message between our user and the website server were encrypted from that point of time, the key had been leaked and thus could have been used to decrypt messages and see everything.

So this is not a secure channel for communication, even though we applied encryption.

It appears that we need a way to distribute the encryption key in a such a way that it doesn’t compromise our secure communication channel. Turns out that this has always been a big problem for humans until relatively recently. For example, during World Word II Germans distributed keys to the infamous Enigma machine using military couriers in books made of easily destroyable paper and ink. They had to re-distribute new sets of keys each month in case some of them were leaked. Distributing keys securely has always been an expensive and problematic aspect of encryption.

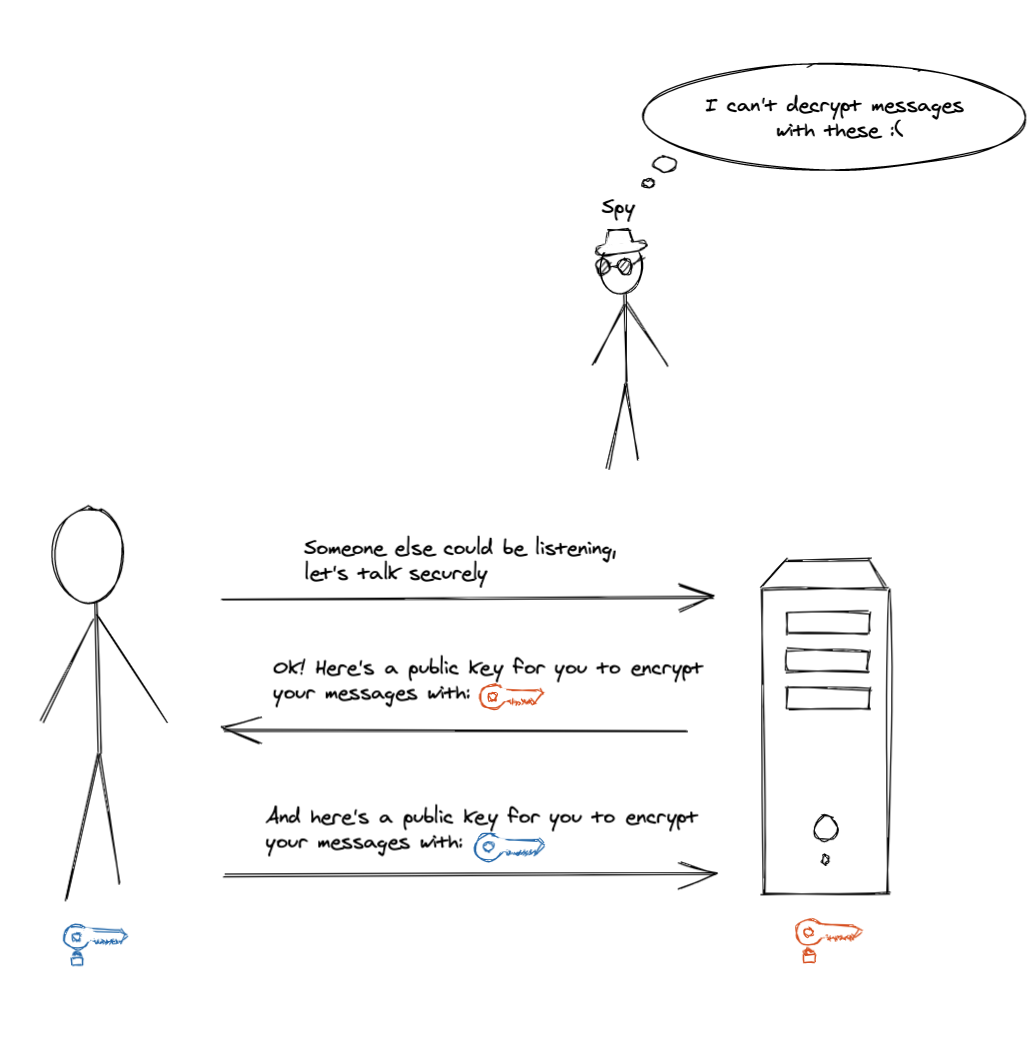

In the 1970s a bunch of smart folks invented RSA algorithm removing the need to distribute a key used for decrypting data by a clever use of mathematics of prime numbers. There was not a single key anymore, but instead a key pair with a public key and a private key. You encrypt data with the public key and decrypt it with private one. Public key can be freely distributed over insecure channels as it doesn’t compromise security – it’s not usable for decrypting data. This is why it’s called asymmetric - one key allows you to only encrypt and another key allows you to only decrypt, you can’t just use the same key both ways.

If we apply this technique in our case, we can now establish secure communication by having our website and user exchange public keys before talking to each other:

Now attackers can see the public keys and the encrypted data we’re sending over the wire, but the keys they see are not usable for decryption, so they can’t really see what our user and the website are saying to each other.

There’s still one problem though. This came with pretty big price — asymmetric encryption algorithms are orders of magnitude slower than symmetric ones. The payload size is also bigger. Ideally we want to keep using the symmetric encryption like in our initial setup, and apply the slower asymmetric encryption algorithm just for the critical part of key exchange.

And turns out this is precisely what a TLS handshake does, if you read carefully through all the steps.

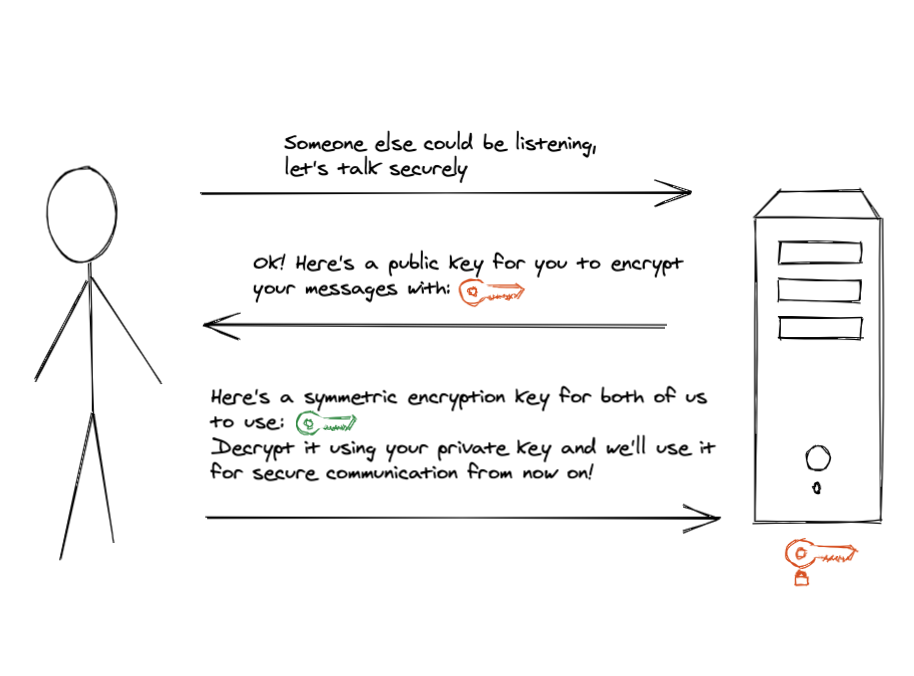

Website first sends us a public key and the asymmetric encryption algorithm it’s using, so the user can encrypt data and send it to the website and only the website will be able to decrypt it! This setup is secure enough for user to send over the symmetric encryption key to the website and then, once the website got it, both parties can now establish a secure channel of communication with symmetric encryption! yay!

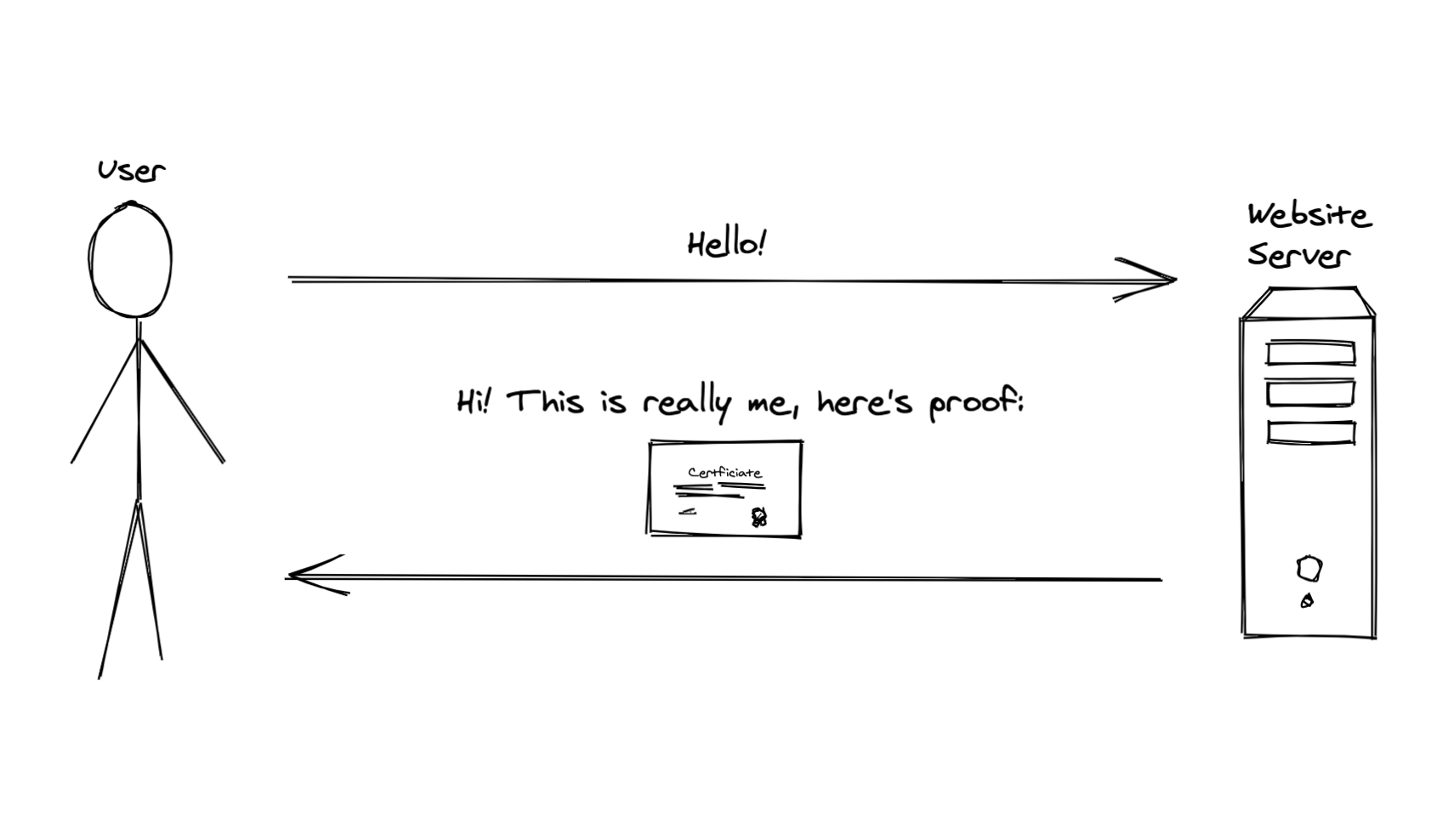

But unfortunately this wasn’t enough to claim success. There’s still one attack angle which we didn’t cover - attackers could “insert” themselves in the middle of our communication and alter the messages! When the user is sending their “hello” over the wire and gets a “hello” back, they need some sort of proof that the party saying “hello” back is actually the website they wanted to talk to, not some sweaty dude in a basement trying to steal some credit card information.

This is where Certificates and Digital Signatures come into play.

Certificates

We can setup a scheme akin to governments issuing passports which are then used for proof of identity. We’ll have the website show us their “passport” before we continue exchanging information with it. We’ll examine the passport to make sure it’s not fake and is not issued by the same sweaty dude in the basement and we’ll know that the website is the real deal. We’ll call those “passports” Certificates and the government issuing them – a Certificate Authority.

But how do we create a digital proof of identity? Turns out RSA comes to the rescue again.

Digital Signatures

We haven’t talked about another awesome feature of RSA yet. Remember how we claimed that you can only encrypt data with public key and decrypt with private one? That’s not entirely true — you can actually flip this process and ENCRYPT data with the private key and decrypt it with public one. How is this useful though, you might ask? Public key is… public so anyone could decrypt the message and see its contents.

Turns out you can use it for signatures! The fact that you are ABLE to decrypt data means that the cipher could only come from the real holder of the private key. If someone else wanted to hack their way into this process and offer you a cipher text obtained with a wrong private key, you’ll be able to tell something is off — your public key doesn’t let you decrypt the data, i.e. when you decrypt the cipher the message doesn’t make any sense!

So knowing this feature of RSA we can now make the website send a private key-encrypted piece of information we’ll call signature in its response to the user’s initial “hello” message. But which private key encrypts this signature and which public key should be used to decrypt it? Previously we’ve established that the website has its own key pair which was used to setup the secure communication channel, but it’s not really usable here — if the signature is encrypted by the same website’s private key, the fact that we can decrypt it doesn’t prove us anything. It could be the same sweaty credit card-stealing person.

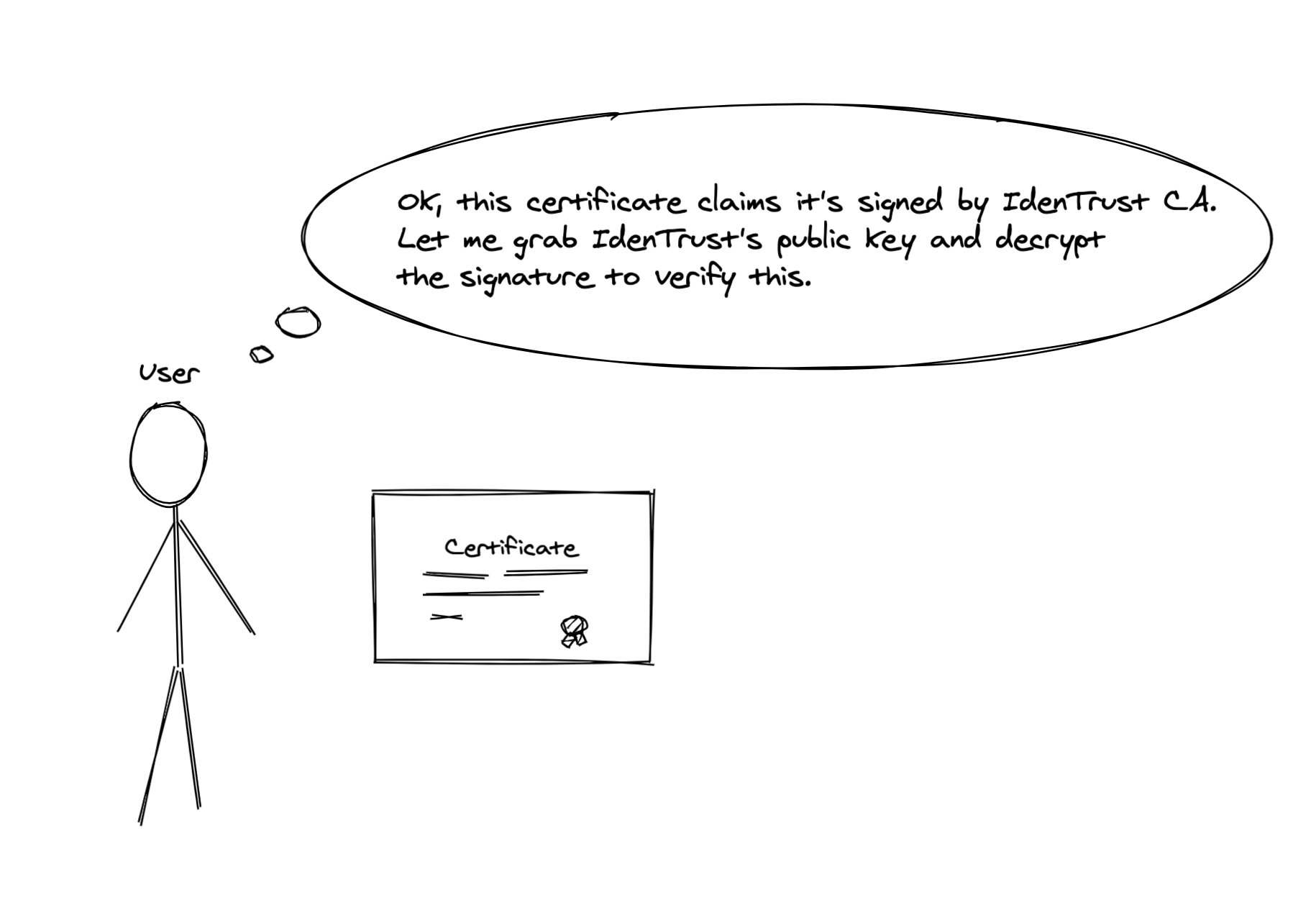

Remember, we’re trying to make this signature a proof of website’s identity, and in our government-issued passports analogy we established a trusted authority figure which we trust — a certificate authority (CA). So let’s ask these CA guys encrypt the website’s certificate contents with their private key and that would be our signature! We’ll make our website include this signature inside the certificate along with the other data it was sending to the user, so the user could then use a known public key of the CA to decrypt the signature thus verifying that the website went to the CA and registered themselves and was given a “passport”. Don’t worry, the user won’t need to keep track of the all known CAs’ public keys – browsers do this for them.

If the user managed to decrypt the signature and what they’ve got matched the certificate contents (including stuff like domain name), that would give them enough proof that some CA indeed issued this certificate to this particular website. There was indeed a government issuing this passport for this website at some point and the government’s seal in the passport matched the user’s expectations.

So now not only our communication channel is secured with encryption, we also have a mechanism for the website to prove their identity to users using digital signatures and certificate authorities.

The user and the website can finally talk in peace, securely.